There’s a valid distinction, which I would make between

the spiritual and the sacred. I see my particular calling as a painter and a

Jew, drawing from the wellsprings of Torah truths, which imbue each and every

day of a Jew’s life. That for me is spirituality put in practical everyday

terms, from laws concerning kosher food to the observance of pilgrim festivals

in the yearly cycle.

Such a fulfillment – termed a mitzvah in Hebrew for its

sense of duty – is far more attainable than any mystic yearning for the sacred

in other world religions. In terms of my art, it means holiness is everywhere,

waiting to be plucked, like the holy apples about which the mystic rabbis of the

medieval age sang to usher in the Sabbath.

One becomes the other and in that transition, a totally

different experience has come into being. That for me is mystical. I think there

is a wondrous spirituality when the creative process is expressed in paint. It

sets us free to soaring new vistas. Chagall said it well – "Painting was as

necessary to me as bread. It seemed like a window I could escape out of, to take

flight to another world." (Marc Chagall, Painter of Dreams, pg.

90).

There is a full-blooded hearty holiness to Jewish faith

that might catch some people unaware. That is part of the distinction, which I

make between the spiritual and the sacred: a Jew performs a mitzvah

gladly – he runs to the opportunity because it is part of his own soul and his

own spiritual reality.

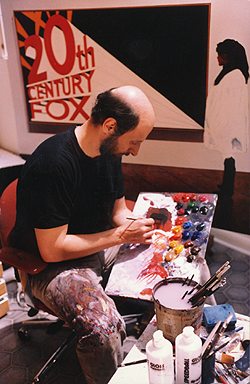

The enthusiastic joy pervades my thinking and quantifies

my art. I think I’m part of a greater artistic tradition whenever I explore the

nuances in life. I enjoy examining details. There is so much information in a

painting that a viewer might lose sight of in a cursory glance while walking

through a gallery.

You can appreciate that there is an insidious compulsion

to religious motivation for someone who is both Jewish and a painter. Like those

who have followed this path before me, I sense that I’m religious and yet I work

in a medium that some Jews with a spiritual inclination would shun.

Artists must wrestle with spiritual values every time

they put their brush to the canvas. "Spirit in its human manifestation is man’s

response to his You. Man speaks in many tongues – tongues of language, or art,

of action – but the spirit is one; it is response to the You that appears from

the mystery and addresses us from the mystery." (I and Thou, pg. 89)

There have been many notable Jewish abstract painter, but

far fewer Jewish realist painters. Two hundred years ago, a Jew who aspired to

be an artist found his calling as an itinerant craftsman, engraving seals on

pewter plates throughout Bohemia, or bookplates in England.

It wasn’t until the Age of Emancipation that Jewish art

blossomed in Europe. Moritz Daniel Oppenheim, Solomon Alexander hart, Camille

Pissarro, Isidor Kaufman and Maurycy Gottlieb all created memorable works with

artistry on par with their non-Jewish counterparts.

A truthful painting survives close reading by evoking

that inherent mystery in our spiritual existence. This observation, I think, is

key to understanding high-realist painting, making painting analogous to poetry,

rather than the novel form – shortened, pithy, succinct and not always

transparent to elucidation on a first reading.

I find a kind of irony, when you contemplate the span of

man’s life from ‘dust to dust’. Our life is dust, a fact I confirm everyday in

the morning prayers. "All the nations are as nothing before You, as it is

written: the nations are as a drop from a bucket; considered no more than dust

upon the scales! Behold, the isles are like the flying dust." (Isaiah

40:15)

A painter deals with dust – materials that have a very

limited life span. A small detail if you ignore everything else will tell you a

lot about the rest. It may seem futile to make such efforts to perfect art. But

we mirror previous history. We do things over and over again, endlessly striving

for betterment.

My optimism makes me see inevitable progress, in spite of

the setbacks of society. The spirituality of our present workday life is

frequently overlooked. Modern man is too busy making money and working hard to

see divine intervention. Quite simply, there’s an up and down to our life –

we’re down here in our busy material world. The spiritual seems to soar far

above us, far beyond our lowly vantage point.

Art can bridge the up-and-down otherness. There is a

closeness to God springing from daily material things… even paint on a canvas.

Think about the meticulous statements concerning the material not the

spiritual in the Jewish morning prayers. Here is an excerpt concerning

the preparation of incense for the altar:

"The balm is no other than resin which exudes from the

balsam trees. The lye of Carshina was used for rubbing on the onycha to refine

its appearance. The Cyprus wine was used in which to steep the onycha to make

its odour more pungent."

You can almost see the priest with mortar and pestle,

grinding the special ingredients for the service. Truly dust is a metaphor for

human life and human endeavor.

With that in mind, I go back to a further metaphor for my

work. A painting is like a child. I encourage it to grow from the dust. Then it

is strong enough to be independent, to stand freely on its own in a world of

adversity. I can’t keep it in my home forever. But I will visit my work three or

four years later to re-examine a painting that I did. When I’m painting a work,

I see it in parts ‘like the flying dust’. To see it in totality, I have to get

away from a painting for a period of time. Then I can view it as you

might.

Barry Oretksy